DICK ROSE CHRISTIAN LIFE, JANUARY 1984 Dick Rose is an aviation and aerospace writer, and the past aviation editor of The Arizona Republic. He attended the University of Washington.

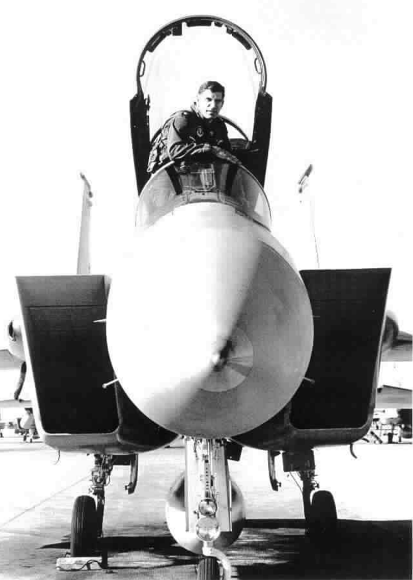

Not long ago, (now) Colonel Kris Mineau, United States Air Force, was taking off from Luke Air Force Base, just outside Phoenix, Arizona, where he served as an instructor pilot in the F-15 Eagle and a squadron commander. Barely off the ground, a violent engine explosion rocked the aircraft and the Eagle caught fire. Quickly he began a turn to get back to the runway. Looking behind him, he saw huge billows of golden flames engulfing the entire rear of the stricken fighter. “Prepare to eject!” his wingman shouted over the radio. Mineau relates, “I had done that once before and it hadn’t worked out very well. I had no desire to try it again. But the fire was really blazing and I wasn’t making much progress activating the engine-bay fire extinguishers. So I asked the Lord to please put it out.”

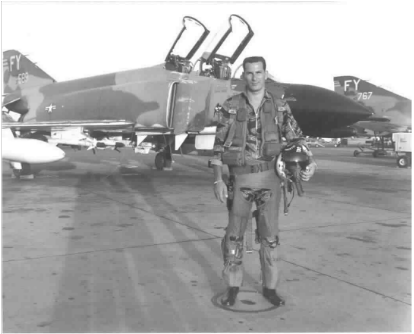

Instead, as the seconds passed, the fire grew. If the fire continued, Mineau realized, it would destroy the airplane before he could get it on the ground. To reduce the fighter’s weight for immediate landing, he jettisoned the full 600-gallon external fuel tank over a clear area. The explosion of the tank impacting the ground vividly recalled a much more horrific scene in Mineau’s mind as he lined up the burning jet with the runway. “I called out to the Lord how He had saved me before, and I asked Him again to put out that fire!” At that instant the fire burned through the underside of the aircraft, allowing the molten mass of engine debris to fall out. With the flames extinguished, Mineau maneuvered the jet to the runway, engaging it like an aircraft carrier to catch an arresting cable with the Eagle’s tail hook. Stopping in a scant 500 feet and surrounded by a throng of fire trucks and emergency vehicles, Mineau gratefully climbed out of the still smoldering $20 million aircraft. “God was just reminding me,” Mineau says, referring to another flight with an almost unbelievable ending. “He was telling me that if He could help me once, He could do it again.” Kristian M. Mineau, 43, born in Berlin during World War II, the son of a German soldier who did not return from the war, a graduate of the U.S. Air Force Academy and a veteran of 100 combat missions over North Vietnam, says that he was a “super macho” pilot who once followed the philosophy of Hugh Hefner rather than the Lord whom he follows today. “I knew all the answers — I thought,” he says.

His amazing story of human transformation began one cold bleak day on March 25, 1969 near the English village of East Dereham. While on a routine air combat training mission, a mechanical malfunction in (then) Capt. Mineau’s F-4 Phantom locked the flight controls. The huge fighter plane and its crew of two plummeted toward the ground at the speed of sound. Mineau quickly discovered that he could not correct the problem. He ordered his rear seat weapons officer, Capt. Mike Hinnebusch, to “punch out” as Mineau initiated the ejection sequence. Instantly, he heard the loud explosion of the rear canopy jettisoning and the rocket motor blasting the rear seat away from the doomed fighter. As soon as Hinnebusch cleared the airplane, Mineau knew he was in deeper trouble, as the automatic sequenced firing of his rocket seat did not happen. Mineau pulled the ejection handle again and again, to no avail. The airplane was now well below the minimum altitude required for a successful ejection — but there were no other alternatives. His ejection system failed to operate because the supersonic wind pressure would not allow the front canopy to separate from the aircraft. Mineau was hopelessly trapped. “I had tried all the known procedures and nothing worked,” Mineau recalls. “I had never been a religious person. But as my life actually passed before me in those last moments with my airplane diving straight into the ground, I cried out, ‘Please God, help!’” “At that very instant, the canopy came off, allowing my ejection seat rocket motor to fire and blow me clear of the airplane. God did it!” he exclaims. “But now there was not enough time for the parachute to open before I would hit the ground. Because of the required sequence of mechanical actions that must take place, the parachute could not deploy for three to four seconds. With my downward velocity of 1,280 feet per second and an altitude below 1,000 feet, there was no chance.” “I remember feeling the tug as the parachute opened in what was later determined to be about half a second. Absolutely impossible from the mechanical standpoint, but it happened.”

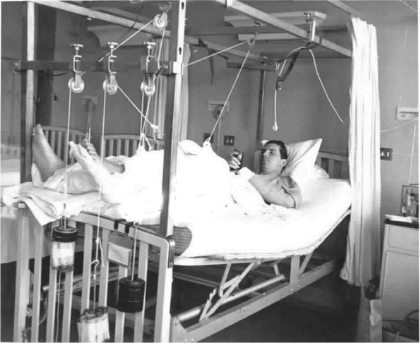

Mineau looked down just in time to see the enormous fireball as his plane hit the ground straight in and exploded. He feared that his parachute would carry him directly into the flames. But when he tried to steer himself to avoid the fireball, his arms would not move. They both were shattered and hanging limp. As Mineau got ready to brace himself for the landing, he discovered that his legs would not move either. They were likewise broken into pieces by the supersonic windblast and useless. He impacted the ground “like a 200-pound rag doll” and could not move. His limbs were strewn in a grotesque pattern and he remembers the heel of his left foot lying beside his face. “I was absolutely helpless,” he says. Mineau lay in an open farm field unable to move or cry out for help, wondering if someone would come in time — before he died. The supersonic wind of 750 mile per hour had broken his limbs as though they were matchsticks, but he was alive. He says it was a miracle. So far, no one has argued the point.

A doctor and rescuers from the nearby village arrived on the scene quickly and, just 30 minutes after the crash, a Royal Air Force helicopter was rushing Mineau to a hospital. A short time later his teammate, Hinnebusch, who had suffered similar injuries, also arrived there. The doctors left Mineau on a hard X-ray table for the first seven hours without treatment. He remembers the agony to this day. “What really got to me was when I was told later that for those seven hours of laying there in total pain, the doctors were just waiting to see whether I would live or die. Unable to administer sedatives for fear of massive internal injuries, they could do little else.” The next day both Mineau and Hinnebusch were put into total traction, all four limbs. Other than medicines and good care, that would be the only treatment the doctors could attempt for the next four months. Their wives, Lura Mineau and Pat Hinnebusch, kept a vigil at their bedside for all that time. They had a five hour round-trip drive from their homes each day, but they were always there. Two things kept Mineau going, he says: “My wife and the doctor’s answer to an all important question I asked him: ‘When will I be able to fly again?’ As I look back, I think that doctor probably stretched the truth a lot when he said that if everything went perfectly, I could expect to fly in one year. I wanted to believe him. Flying was my life.” “I worked on the power of positive thinking, and believed that I could get the job done by myself. It was like I was saying, ‘Thanks, Lord, for Your help. But I can handle things from here on. I’ll call on You again when I need You.’ You see, I didn’t realize yet what God expected of me, but I sure found out.” At the end of the four agonizing months, Mineau was put in a body cast and flown with his family on a medical evacuation aircraft to MacDill Air Force Base in Florida where he had trained in the F-4. Upon landing, the aircraft was met by an old friend and former squadron commander, Lt. Colonel “Pat” Patterson. His presence and sincere greetings with housing and transportation for the family made Mineau appreciate that however bad things are, “the Air Force takes care of its own.” But Mineau could not know what lay just over the horizon. A week after arriving in the States, something happened that would test his faith and shatter his dreams of ever flying again. “When they took my body cast off, I knew something was drastically wrong. My limbs drooped like they were made of rubber. The looks on the faces of the doctors only verified my instincts,” he remembers. The traction and body cast had not worked. The breaks in the bones had not healed, and Mineau would have to undergo a series of major surgical procedures to rebreak and reset most of the bones. The doctors estimated that the process would require another year, and they were not overly optimistic about the results. Ever flying again was out of the question. “I was physically and spiritually bankrupt. All of my positive thinking and all my plans for the future were destroyed. My faith in myself was gone,” Mineau says. Then, as the doctors left to prepare for the first of many surgeries, something happened that would change Mineau’s life and provide a hope he didn’t know existed. A fellow Air Force officer — wearing the cross of a chaplain and the wings of a pilot — walked into Mineau’s hospital room. . “He was smiling from ear to ear,” Mineau recalls. “I thought to myself, What right does he have to be so happy? and was just about to tell him where to go, but I didn’t. After all, he wasn’t just a chaplain, he was a fellow aviator and obviously made of the right stuff.”

The chaplain, Major Jim Holmes, turned out to be an Air Force Reservist on his two weeks of annual active duty. He had just “bumped into” Lt. Colonel Patterson who then asked him to visit Mineau. Holmes shared how he had flown bombers during World War II, “had seen the light” — Whatever that was, thought Mineau — and entered the ministry. After hearing Mineau’s story he said, “Boy you sure are lucky.” “It was more than luck, Chaplain,” Mineau replied flexing his self-perceived religious brilliance, “It was a miracle.” He then explained how he had called on God to help him — and how, indeed, He had. “You believe in God?” Holmes asked. “Of course,” Mineau said. “What do you think I am, a heathen?” “Well, this is a miracle — a fighter pilot that believes in God,” Chaplain Holmes bantered back. “But what about Jesus? Do you believe in Jesus Christ?” Mineau thought, “How did I ever get trapped into this conversation?” He had never had much love for “religion,” because he felt it had been forced on him as a child. He knew that his Sunday School teachings said that Jesus was the divine Son of God, but he did not believe it. So he told the chaplain what he really believed: that Jesus was just a good and honest man who was like everyone else except that He had chosen to preach the word of God. “If Jesus was so good, then why was He executed on the cross, the worst form of death ever devised by man?” Holmes countered. Soon Mineau found himself deeply engaged in a conversation about Jesus Christ and the meaning of who He truly is. Years of cobwebs began to wisp away in his mind. “You mean it doesn’t matter who or what you are, as long as you personally accept Jesus and believe that He died to pay the price for your sins on the cross?” he asked the chaplain. “That’s right,” Holmes answered, “He even died for the North Vietnamese.” My worst enemy, thought Mineau. But that makes sense! I can believe that. “Suddenly,” Mineau says, “My mind was flooded with a vision of Jesus on the cross. I felt Him saying to me. ‘I did this for you.’ I felt a power flowing through me and, for the first time, I understood in my heart all the things that I knew in my head about Jesus. I sensed all my failures and sins being forgiven. A deep warmth and a wondrous love enveloped me that I had never before experienced. I was on fire from the top of my head to the bottom of my feet. There I was — the rough, tough, bar room brawling fighter pilot — crying like a baby because I knew that Jesus loved me.” “It was an indescribable event. In what seemed like an instant, all the doubts in my life were erased and I felt totally free. Suddenly, God was no longer a cold impersonal religion; He was vibrantly alive through the reality of Jesus Christ.” That night when Lura came to visit, Mineau shocked his wife by confiding to her his experience with Christ. But neither his wife, nor a few close friends that he tried sharing with, had any appreciation for his “profound revelation.” He decided it would be “best not to tell anyone else if I valued my friends and my Air Force career. Little did I realize that this was the beginning of a whole new life for me.” However, his new life started painfully with many hours under the surgeon’s scalpel.

“After extensive surgery, the doctors were amazed at my recovery. Within a month I was walking again. Not very well, mind you, with multiple casts and crutches. But at last I had made progress and was in control of my life. I was on the way back.” As soon as he could get on outpatient status, Mineau and his wife joined “one of the most fashionable churches in town.” He says he “felt obligated to the Lord to at least attend church again as long as it didn’t tie up too much of my life. I did not have the total message yet, but it was soon to come.” As the one year goal of flying passed by, the left leg developed into another non-union and the doctors began to consider amputation. “If that doesn’t get a fighter pilot’s attention, nothing will,” says Mineau. Then of all things, the Mineau family got new neighbors in military base housing who were deeply committed Christians. As they exuberantly shared their experiential faith in Christ, Mineau realized that he was not the only person on earth to have personally encountered the risen Savior. In fact, he began to understand that this was the normal biblical Gospel message, to receive Christ personally into one’s heart and to live your life for Him. On July 4, 1970, Kris Mineau made, what he calls, a “Declaration of Dependence” on the Lord Jesus Christ with a decision that he now says “made me a different person, forever. Although I still could not kneel because of my injuries, I humbled myself before God and prayed simply, “Lord, I no longer want to do the things I want to do but, rather, the things You want me to do. I want to live my life for You.” “The moment I finished that prayer I had an experience that defies my human comprehension. A sound of pure energy, like the hum of a giant dynamo, filled my bedroom. Through my body flowed the warmth of the same Presence I had encountered in the hospital a year before. Then I heard an audible voice.” “This voice was the most authoritative and yet the most loving I have ever heard. It seemed a million light years away, yet it totally surrounded me with these words: ‘Welcome home, prodigal son. I have waited for all eternity for you to make this decision. Trust in Me, and your leg will be healed. For you it will take time but that is the only way I can get you where I want you to be.’”

From that moment on, Mineau says he was a “new” person. Soon his wife came to personal faith in Christ. But the next four years would be difficult. A long series of operations were necessary to correct the bones that had healed crooked. However, this gave Mineau much time to read and study the Bible for the first time in his life. Through steady church involvement, he learned how to apply biblical principles to every day life. He also found that God could use him in many ways to reach others with God’s message of love and redemption. One of those opportunities uniquely came during follow-up surgery at the Air Force Medical Center in San Antonio, Texas. Upon arrival, he found his hospital roommate to be none other than Mike Hinnebusch who was undergoing treatment at the same time. Hinnebusch had also encountered setbacks in recovering from his injuries and although he had been deeply “religious” before the accident, he had now come to doubt God’s existence. Mineau gladly shared his experiences with his friend and fellow crippled aviator. “I believe that those two weeks marked a turning point in Mike’s life,” Mineau says. “He now deeply loves the Lord and went on to pursue a very successful non-flying career in the Air Force, promoted ahead of schedule and attaining the rank of Colonel.” As Mineau recovered from his injuries, he was assigned to non-flying duties as the Air Force permanently grounded him from flying status. While serving as an academic instructor at the Air Force Academy, he sensed the lore of flight still to be in his heart and decided to make one final thrust at regaining his flying career. He prayed, confiding to God his desire to fly again but asking for His will to be done, regardless. The first flight surgeon he approached with the request shook his head and offered no hope. But Mineau was determined. “They didn’t know Who I had on my side,” he says.

Six months later — and after what seemed like hundreds of examinations and evaluations — the long-awaited decision was made. On August 28, 1974, the Surgeon General of the Air Force approved Kris Mineau to be medically fit for flight status. And on January 1, 1975 he received orders, signed by the Chief of Staff of the Air Force, returning him to duty as a pilot. “There is no other word to describe what happened to me; it was truly a miracle. By all rights I should never have flown again,” Mineau says. But his return to flying was not without another reminder “from above.” Mineau was sent to Holloman Air Force Base, New Mexico, for some warm-up flights in the T-38 supersonic jet fighter trainer before going back to the F-4 Phantom. His first flight “just happened” to be scheduled for Tuesday, March 25, 1975 — exactly six years to the very same day of the week, after his crash in England. When he arrived at the preflight briefing he found that the take-off time was set for 4:30 p.m., the exact same local time of his crash. “It isn’t difficult to sweat when you are wearing a flight suit, but a cold sweat is a little unusual,” he says. But that isn’t the end of the story. Finally, wearing the flight suit, parachute and the helmet that were like old friends from long ago, he walked out to the flight line to climb aboard the first fighter aircraft he had flown in six years.

As Mineau climbed the ladder to the cockpit, he paused to look at the sleek form of this airplane that was to take him on one of the most memorable flights of his career. His attention was directed to the number painted on the tail of the airplane, the aircraft serial number — 898 — the same serial number as the plane he had watched crash into the English countryside exactly six years before. “Now if you think those circumstances are just coincidence, you had better think again,” Mineau says, remembering his two dramatic escapes from death. Today, Kris and Lura Mineau, the parents of four children, live just outside of Phoenix, Arizona. “The Lord always finds a way to remind me,” he says. “I know for certain that I have a working relationship with ‘The Chief Pilot.’ I’m really the co-pilot!”

Loading Page...

Loading Page...